Real and Sustainable: An Update

Just prior to the release of the May 2013 employment, report, we wrote in our June 3, 2013, Weekly Economic Commentary: Real and Sustainable, that in the coming months:

“Federal Reserve (Fed) policymakers must decide if the recent pace of job creation-on average, the economy added 175,000 per month over the past year-and/or the drop in the unemployment rate (from 10.0% at the peak in 2010 and from 8.2% in May 2012) was ‘real and sustainable’ to warrant a tapering of QE.”

“Real and sustainable” was also a phrase used by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke at his now (in)famous testimony before the Joint Economic Committee (JEC) of Congress on May 22, 2013. Answering a question about when the Fed would begin unwinding QE, Bernanke said:

“As the economic outlook and particularly the outlook for the labor market improves in a real and sustainable way, the committee will gradually reduce the flow of purchases.”

Bernanke used similar words answering questions at the press conference following the June 18 – 19 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting.

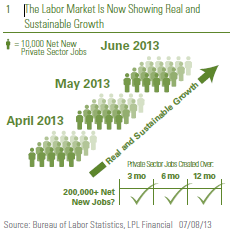

Now, with both the May and June 2013 jobs reports, as well as the June FOMC Meeting and Fed Chairman Bernanke’s press conference in the rearview mirror, financial markets have largely embraced the notion that the Fed will begin tapering QE sometime this fall. Payroll employment in the private sector in both May and June 2013 exceeded expectations, and the job gains reported for April 2013 and May 2013 were revised markedly higher with the release of the June 2013 data. As a result, the private sector economy has added about 200,000 net new jobs per month over the past three, six, and 12 months [Figure 1]. It is pretty clear that the market, especially the bond market, thinks that adding 200,000 jobs per month is “real and sustainable.”

Of course, Fed policymakers are not only looking at the number of private sector jobs being created each month. In early March 2013, FOMC Vice Chair Janet Yellen — who is a leading candidate to replace Bernanke as Fed Chairman in 2014 — said that she was looking at a number of indicators on the labor market and economy. These included:

- The unemployment rate;

- Payroll employment;

- The hiring rate;

- Layoffs/discharges as a share of total job separations;

- The “quit” rate as a share of total job separations; and

- Spending and growth in the economy.

Tracking the Labor Market: Not Quite There Yet

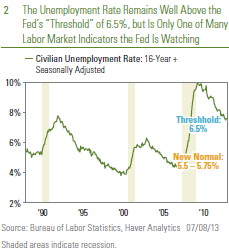

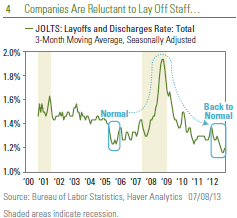

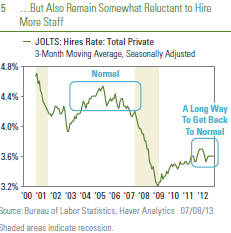

Figures 2 – 5 show the labor market indicators mentioned by Bernanke last week and Yellen in early March 2013. A quick review of the figures suggests that while job growth has been “real and sustainable,” several of the other key measures the Fed is monitoring are not yet sending the same signal. Yellen and Bernanke — two of the three FOMC members of the “center of gravity” at the Fed — are probably not yet ready to begin scaling back QE.

- While down from the peaks seen during the Great Recession of 2008 – 2009, the unemployment rate, at 7.6% in June 2013, remains well above the 6.5% threshold for raising rates, and also well above the 5.50 – 5.75% rate the FOMC forecasts as the new “normal” unemployment rate. In his prepared comments to the press just prior to his FOMC press conference on June 19, 2013, Bernanke said that QE would likely end in mid-2014, when the unemployment rate hits 7.0%.

- The economy is now consistently creating 200,000 jobs per month, and has been over the past 12 months.

- At 3.6% in April 2013, the latest data available, the hiring rate — the level of new hiring as a percent of total employment measured from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) data remains depressed, and well below the 4.5 – 5.0% hire rate seen prior to the onset of the Great Recession in 2007. In her March 4, 2013 speech, Yellen noted, “the hiring rate remains depressed. Therefore, going forward, I would look for an increase in the rate of hiring.” The May JOLTS report is due out this Tuesday, July 9, 2013.

- In that same speech, Yellen noted “layoffs and discharges as a share of total employment have already returned to their pre-recession level”. Indeed, Figure 4 shows that the discharge rate, at 1.2% in April 2013, is very close to an all-time low. A good proxy for this metric is the weekly readings on initial claims for unemployment insurance and the monthly Challenger layoff data, both of which continue to show that companies are reluctant to shed more workers at this point in the business cycle.

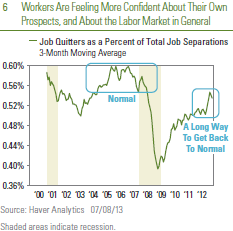

- The quit rate measures the percentage of people who leave their jobs voluntarily, presumably because they are confident enough in their own skills — or in the health of the economy — to find another job. In the three months ending in April 2013 (the latest data available), 53% of the people who were separated from their jobs (laid off, fired, retired, or left voluntarily) were job quitters. This reading was just below the 54% readings in February and March 2013, which were the highest readings on this metric since mid- 2008. Even at 54%, this metric remains well below its pre-Great Recession norm of 56 – 60%. Commenting on this metric in her March 4, 2013 speech, Yellen noted “a pickup in the quit rate, which also remains at a low level, would signal that workers perceive that their chances to be rehired are good — in other words, that labor demand has strengthened.”

- The final metrics mentioned by Yellen — consumer spending and overall economic growth — both remain well below average, and indeed still point to an economy that is still running at around two-thirds speed.

GDP and Jobs: Why the Disconnect?

Since the end of the 1981-82 recession, the economy has seen four periods when it has consistently created 200,000 or more private sector jobs per month:

- Mid-1980s

- Late 1980s

- Mid-1990s through the end of the decade

- Early 2006

On average, when the economy has consistently produced 200,000 jobs over a 12-month period, economic growth — as measured by growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) — has averaged between 4.5% and 5.0%. Today, the economy is struggling to grow at 2.0%, and our forecast is that growth is likely to be near 2.0% over the rest of 2013. What has caused the disconnect between job and GDP growth, and does better job growth mean better economic growth in the period ahead?

In general, the economy leads job growth, not the other way around. The timing of the economic recoveries and labor market recoveries over the past 20 years is helpful in illustrating this point. Coming out of the 2007 – 2009 Great Recession, the economy bottomed out in June 2009, while the labor market did not begin creating jobs regularly until spring 2010. The same pattern played out coming out of the mild recession in 2001. The recession ended in November 2001, but the economy did not begin to consistently create jobs until the summer of 2003. The 1990 – 91 recession ended in March 1991. The private sector economy did not begin creating jobs regularly until a year later, in the spring of 1992.

The recent disconnect between private sector job growth and the performance of the economy can be partially traced to several factors. First, the severity and composition of the Great Recession was unique in its scope, and recent financial-led recessions in other countries suggest that economies recover more slowly from recessions caused by severe financial crisis. Restrictive fiscal policy at both the federal and state and local levels is also a culprit of the disconnect between 200,000 per month job growth and an economy growing at only around 2.0%. In the first half of 2013, the economic drag from fiscal policy (less spending and higher taxes) likely shaved around 2.0% from GDP. In addition, the recession in Europe and the sharp slowdown in emerging markets have sharply curtailed our export growth, which in turn, puts downward pressure on GDP growth.

The bottom line is that job creation tends to lag the overall economy, and that the recent job gains likely do not portend stronger economic growth in the coming months. Any uptick in economic growth over the next few quarters would likely be the result of an easing of fiscal pressures or improvement in the economies in Europe and emerging market countries.

Closer Look: Labor Market Surveys

- A survey of 60,000 households nationwide — an incredibly large sample size for a national survey — generates the data set used to calculate the unemployment rate, the size of the labor force, part-time and full-time employment, the reasons for and duration of unemployment, employment status by age, educational attainment, and race. The “household survey” has been conducted essentially same way since 1940, and although it has been “modified” over the years, the basic framework of the data set has stayed the same. The last major modification to the data set (and to how the data is collected) came in 1994. To put a sample size of 60,000 households into perspective, nationwide polling firms typically poll around 1,000 people for their opinion on presidential races.

- The headline unemployment rate (7.6% in June 2013) is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed (11.8 million in June 2013) by the number of people in the labor force (155.8 million). The civilian population over the age of 16 stood at 245.5 million in June 2013. A person is identified as being part of the labor force if they are over 16, have a job (employed), or do not have a job (unemployed) but are actively looking for work. A person is not in the labor force if they are neither employed nor unemployed. This category includes retired persons, students, those taking care of children or other family members, and others who are neither working nor seeking work.

- In June 2013, the labor force was 155.8 million, which consists of 144 million employed people and 11.8 million unemployed people. Another 89.7 million people over the age of 16 were classified as not in the labor force. The 155.8 million people in the labor force plus the 89.7 million people not in the labor force is equal to the civilian population over 16, 245.5 million.

- The payroll job count data is culled from a survey of 440,000 business establishments across the country. The sample includes about 141,000 businesses and government agencies, which cover approximately 486,000 individual worksites drawn from a sampling frame of Unemployment Insurance (UI) tax accounts covering roughly 9 million establishments. The sample includes approximately one-third of all nonfarm payroll employees. From these data, a large number of employment, hours, and earnings series in considerable industry and geographic detail are prepared and published each month.

___________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments and exports less imports that occur within a defined territory.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Stock investing involves risk including loss of principal.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), a committee within the Federal Reserve System, is charged under the United States law with overseeing the nation’s open market operations (i.e., the Fed’s buying and selling of United States Treasure securities).

Quantitative easing is a government monetary policy occasionally used to increase the money supply by buying government securities or other securities from the market. Quantitative easing increases the money supply by flooding financial institutions with capital in an effort to promote increased lending and liquidity.

___________________________________________________________________________________

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC

Leave a comment