Portfolios are likely to enjoy more independence from policymakers in 2014 compared to 2013, when the markets and media seemed to obsess over policymakers’ actions both here and abroad, as noted in our Outlook 2014: The Investor’s Almanac. Despite our view that the economy and markets are likely to become more independent of policymakers this year, actions (and words) of central banks always have (and likely always will) some impact on global economies and financial markets.

Every year, we devote many pages in this publication and others to discussing the United States’ central bank — the Federal Reserve (Fed). We have also written extensively about the Eurozone’s central bank, the European Central Bank (ECB); China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China; and more recently the Bank of Japan (BOJ), Japan’s central bank. But what about the other prominent central banks around the globe?

- Have they been lowering or raising rates?

- What are their concerns?

- What indicators do they watch?

- What are their views of economies beyond their own?

The political independence, as well as the relative transparency, of each of the banks is of course also of keen interest to market participants. We plan on examining these issues in future editions of the Weekly Economic Commentary.

Figure 1 details 15 central banks, representing 19 of the top 20 economies in the world. These central banks set monetary policy for nearly 90% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP). What they do and say matters, even in years where policy is likely to take a back seat to portfolios, as we expect to be the case in 2014.

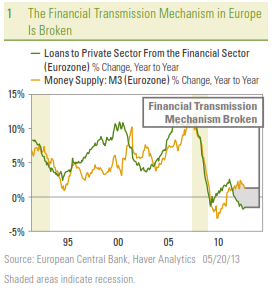

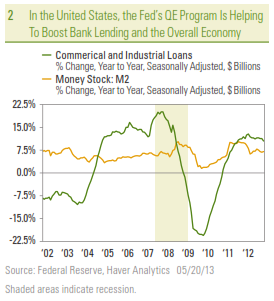

At first glance, it may seem that developed market central banks have all been aggressively cutting rates since the onset of the financial crisis and Great Recession in 2007. However, while the ECB, the Fed, the BOE, and the BOJ have been aggressively easing policy over the past five years or so, central banks in several large developed economies have raised rates over that time. Geography and exposure to commodity prices were keys to most of these policy shifts. The divergence in central bank policies within the developed world, and between the developed world and the emerging market economies, has created risks and opportunities across the investment spectrum — equities, bonds, commodities, and currencies — for active managers investing in many of these regions and asset classes.

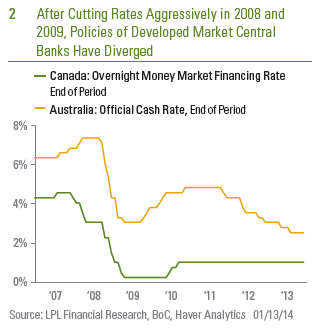

For example, the Bank of Canada (BOC), along with the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), and South Korea’s central bank, the Bank of Korea, have all raised rates since 2008, and all have either close ties to China and the relatively strong emerging market economies, or have big exposure to commodity prices. Most — but not all — emerging market central banks have raised rates at least once since 2009.

Commodities, currencies, and China were key drivers of policy in this group. For example, in October 2009, Australia’s central bank, the RBA, raised rates by 25 basis points, noting that the downside risks for the economy had waned, the risk of rising inflation had increased, and that “Growth in China has been very strong, which is having a significant impact on other economies in the region and on commodity markets.” The RBA continued to raise rates over the next 12 months, but has been cutting rates since late 2011, citing a slowdown in Europe and China, moderating inflation, and a decline in commodity prices.

The BOC waited until June 2010 to raise rates, citing “strong momentum in emerging market economies” and forecast that Canada’s economy would return to “full capacity” by the end of 2011. Canada raised rates three times (by a total of 75 basis points) in 2010 but has not made a change to policy since late 2010. Commodity prices (lumber, energy) are key components of the Canadian economy, which has strong ties to China and Asia as well.

Similarly, the Bank of Korea (BOK) began raising rates in mid-2010, noting “emerging market economies have sustained their favorable performance” and “upward pressures (on inflation) are expected to build continuously owing to the increase in demand-pull pressures associated with the continued upturn in economic activity.” The BOK raised rates by a total of 125 basis points between mid-2010 and mid-2011, but has generally been cutting rates since then. Korea’s economy is closely linked to China’s and Japan’s.

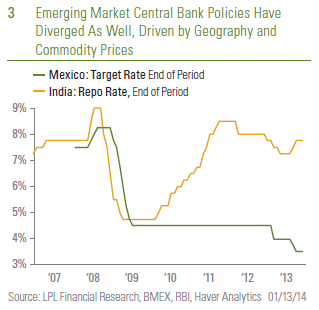

Among the seven emerging market central banks on our radar, six have raised rates at least once since 2009, including the People’s Bank of China, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Brazil’s central bank, and the central banks of Turkey, Russia, and Indonesia. Most of these rate hikes were the result of higher-than-expected inflation readings and/or concern over the value of the local currency. Russia’s central bank, Bank Rossii, has increased rates by just 50 basis points since 2011, a far less aggressive round of tightening than at any of the other emerging market central banks on our list. Why? Russia’s economy was more severely impacted by the crisis in Russia’s next door neighbor Europe than most of the other major emerging market economies. Mexico’s central bank, the Banco de Mexico (Banixo), has been cutting rates since early 2013. Mexico’s economy, of course, is closely tied to the U.S. economy, which has been sluggish. A stronger peso (Mexico’s currency) and stable inflation provided the scope to cut rates.

For many of these countries, the latest round of rate hikes is the second since 2009. For example, Brazil raised rates between mid-2010 and mid- 2011, eased rates as the European financial crisis worsened in 2011, and then began raising rates again in mid-2013. Inflation was the primary catalyst each time. India’s experience has been similar. India began raising rates in early 2010, citing a weakening currency and higher-than-expected inflation. After raising rates throughout 2010 and 2011, the RBI began cutting rates in 2012 and into early 2013, but recently, as the Fed began to consider scaling back its quantitative easing (QE) program, the RBI began raising rates, citing weakness in the rupee, India’s currency. Indonesia’s experience with rates over the past four years is similar to the RBI’s and Brazil’s central bank.

China’s central bank was quick to tighten in 2010 and 2011, citing rising inflation pressures, but stopped raising rates by mid-2011. By mid-2012, concerned with a slowdown in export growth, the PBOC cut rates, against the backdrop of decelerating inflation.

Looking ahead, with the Fed now in the process of scaling back or tapering, its QE program, and the BOE poised to begin to reduce its QE program, the policy divergences among the world’s major central banks are likely to intensify in 2014. This will create risks to global economies, investments, and currencies, but opportunities as well. We will continue to monitor what these banks do and say throughout the year, keeping in mind that portfolios are likely to matter more than policy in 2014.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Stock investing involves risk including loss of principal.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments and exports less imports that occur within a defined territory.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), a committee within the Federal Reserve System, is charged under the United States law with overseeing the nation’s open market operations (i.e., the Fed’s buying and selling of U.S. Treasury securities).

Quantitative easing is a government monetary policy occasionally used to increase the money supply by buying government securities or other securities from the market. Quantitative easing increases the money supply by flooding financial institutions with capital in an effort to promote increased lending and liquidity.

Tapering refers to the Federal Reserve (Fed) slowing the pace of bond purchases in their Quantitative Easing (QE) program. To execute QE, the Fed purchases a set amount of Treasury and Mortgage-Backed bonds each month from banks. This inserts more money in the economy (known as easing), which is intended to encourage economic growth. Lowering the amount of purchases (tapering) would indicate less easing of monetary policy.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC