As has been the case since late 2008 when the Federal Reserve (Fed) began its quantitative easing (QE) program, there has been a great deal of concern lately among some market participants that the dollar is on the verge of collapse, but is that a likely scenario?

Corporate America More Concerned With Rising, Not Falling Dollar

455 of the 500 corporations in the S&P 500 Index have reported results for the first quarter of 2014 and, in many cases, have also provided guidance on their operations in the current quarter and for the remainder of the year. As always, when discussing the business environment, corporate management cited swings in the value of the dollar versus the currencies of the nations in which they do business, but none sounded the alarm about an imminent collapse in the dollar. Indeed, many were more concerned about the value of the dollar rising. Why? Because a rising dollar makes U.S. goods and services more expensive to foreign buyers Fed Influence

Similarly, in the five press conferences held by former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke and current Fed Chair Janet Yellen since early 2013 following Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings, the value of the dollar was not mentioned once. The last time the dollar came up at a Fed Chair’s post-FOMC press conference was in December 2012, when then- Fed Chairman Bernanke was asked if the size of the Fed’s balance sheet following QE threatened the credibility of the dollar as the world’s leading currency. Bernanke’s response: We’re not the only central bank that has increased the size of its balance sheet. The Japanese, the Europeans, the British have all

done the same, and very much more or less to the same extent in terms of the fraction of GDP, and I think the sophisticated market players and the public understand that this is part of a collective need, a need to provide additional accommodation to weak economies and not an accommodation of fiscal policy. Bernanke was pointing out here that the value of the dollar is set in global markets, and that other central banks were pursuing the same policies as the Fed, in some respects cancelling out the impact of the Fed’s QE program on the value of the dollar.

The Key Drivers

Aside from two periods in the early 1980s and late 1990s, the US dollar has been declining since it went off the gold standard in the early 1970s. As Bernanke noted in late 2012, the value of the dollar is set in the open market, although the Fed, Congress, and the President can have an impact on the dollar. Of the three, the Fed probably has the most direct impact on the value of the dollar, as it sets short-term interest rates, which often have a big influence on the value of a nation’s currency. The Fed’s QE program, which is winding down and set to conclude by year-end 2014, has increased the number of dollars in the global economy. The law of supply and demand suggests that the greater the supply of an item, the lower the price, so at the margin, QE has put downward pressure on the dollar. The value of the dollar has declined 8% relative to the currencies of our major developed market trading partners (the Eurozone, Canada, Japan, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Australia, and Sweden) since the onset of the first round of QE in November 2008 [Figure 1]. The 8% drop in the 5.5 years since the onset of QE1 (about 1.5% per year) is about double the 0.75% pace of annual depreciation seen in the dollar between the early 1970s and late 2008, when the first round of QE began. The weaker dollar has, at the margin, made our exports more attractive, pushed up the costs of goods we import, and, most importantly, pushed the prices of globally traded commodities higher. It has not eroded global market participants’ appetite for Treasury notes and bonds however. As of May 9, 2014, the yield on the 10-year Treasury note was near 2.65%. At the start of QE, the yield on the 10-year Treasury note was near 3.25%. As the Fed begins to wind up QE, and begins to debate when to begin raising rates, the influence of QE on the dollar should begin to fade, and, at minimum, the pace of the dollar’s depreciation should return to its pre-2008 pace of around 0.7% per year. But what about our major trading partners, whose monetary policies Fed Chairman Bernanke cited in late 2012?

Global Monetary Policy Influence

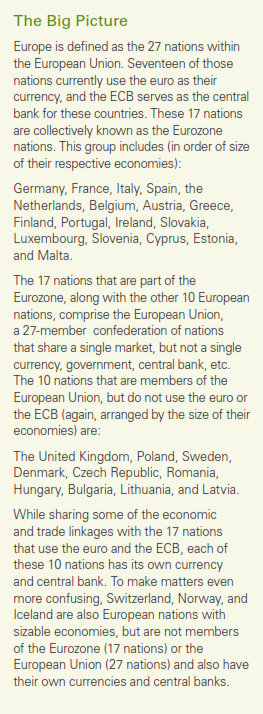

The monetary policy of nations outside the United States may also have an influence on the value of the dollar in world markets. As we noted in our Weekly Economic Commentary: Central Bank Pulse (May 5, 2014), global central bank policies have diverged in recent years, after mainly moving in the same direction — easier policy — between 2007 and 2011. Among our largest trading partners, both the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of Japan (BOJ) are easing and poised to do more, while the Bank of England (BOE) is likely the next major central bank to consider exiting QE and beginning the process of normalizing rates. The Bank of Canada — the central bank of our largest trading partner—looks to be on hold for the foreseeable future. The dynamics of central bank actions also suggests a slower pace of depreciation in the dollar (and even some possible appreciation) in the period ahead, not a collapse in the value of the dollar as some may fear.

Foreign Selling?

Another concern often raised by those predicting an imminent collapse in the dollar is that countries with large holdings of Treasuries (and dollars) like China, Japan, and, to a lesser extent, Russia, will suddenly sell all of these holdings in the open market all at once for either political reasons (disagreements with the U.S.) or economic reasons (loss of confidence in the U.S. economy, the Fed, Congress etc.). Our view remains that a major shift in China’s or Japan’s or even Russia’s holdings of dollars and Treasuries is unlikely anytime soon given the tight trade linkages between the countries. China and Russia depend on U.S. goods and services to help advance their own economies, making it difficult for them to operate their economies efficiently without dollar holdings to fund purchases of goods and services. Over time (years and decades, not days and weeks), economies outside the U.S. are likely to continue to move away from the dollar and Treasuries — a trend that has already been in place for some time now — but a move out of dollar holdings all at once would not be in the best economic interest of the selling country.

“Twin Deficit” Influence

Trade policy, broad economic policy, and even foreign policy—set by Congress and/or the President—can also have an impact on the value of the dollar. Our “twin deficits” (trade and budget, see Figure 2) have put downward pressure on the dollar over the past several decades. However, both the budget and trade deficit are narrowing, the budget deficit since 2009 and the trade deficit since mid-2005. Should these trends persist, they will tend to support the value of the dollar, suggesting, at minimum, a slowdown in the rate of dollar depreciation that we have seen since the start of the QE era in 2008. Since the United States is the world’s largest economy, most global trade is denominated in dollars, making the dollar the world’s “reserve currency.” As noted above, central banks and governments of most nations outside the United States hold reserves in dollars, although the rise of China’s economy and the sheer size of the Eurozone’s economy has eroded the dollar’s“reserve currency” status in recent years.

Still, the dollar is still viewed as a “safe haven” currency, as are U.S. Treasury notes and bonds, which, of course, are denominated in dollars. In times of economic and political uncertainty around the globe, the dollar normally rises in value, as investors must use dollars to purchase Treasuries, the ultimate “safe haven” asset. While our “twin deficits” and the Fed’s actions to stimulate the economy have put downward pressure on the dollar, the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency, and the United States’ position as the world’s largest economy and largest exporter, with its diversified and dynamic economy and labor force, suggests that a sudden sharp decline in the value of the dollar is unlikely. The recent ramp up in energy production in the U.S., sometimes referred to as the “energy renaissance,” has aided in reducing our dependence on foreign oil and helped to reduce our trade deficit as well. In the next few months and quarters, the dollar may appreciate as the economy accelerates and the Fed moves closer to ending its quantitative easing program and begins to raise rates. In the longer term, however, we continue to believe the dollar will slowly depreciate over time — continuing the trend that has been in place since the early 1970s, but at a pace that will not undermine the nation’s health or its role as a global economic power.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial. To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.