Several key reports on the state of the housing market are due out this week (February 24 – 28, 2014), most of which will likely be negatively impacted by the colder and snowier-than-usual weather in much of the nation over December 2013 and January 2014. The data due this week include:

- Case-Shiller Home Price Index for December 2013;

- New Home Sales for January 2014;

- Pending Home Sales for January 2014; and

- Housing Contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) for Q4 2013.

The weather will eventually return to normal, but market participants are likely to be asking: Once the weather improves, will the housing data continue to feel the pinch of higher mortgage rates over the rest of 2014?

Solid Supports

The recent rise in mortgage rates — from just under 3.50% (for a conventional 30-year loan) in May 2013 to a recent reading of just over 4.25% — has led to widespread fears that the housing recovery will come to a grinding halt. Those fears appear to be overdone, in our view, as almost all of the factors supporting an ongoing recovery in housing remain in place. However, the rise in rates will likely slow the pace of the recovery somewhat.

In general, the housing market hit bottom in early 2009, and moved sideways between early 2009 and late 2011 before picking up momentum at the start of 2012 (please see “Location, Location, Location”). Until housing added 0.3 percentage points to overall GDP in 2012, housing construction (the most direct way housing impacts economic growth as measured by GDP) had not been a significant, sustained contributor to economic growth since 2005. The lack of participation from housing has been one of the main reasons for the sluggish economic recovery, along with the severe cutbacks in state and local governments.

When we last wrote in depth on the housing market in mid-2013, we forecast that “despite the recent rapid rise in rates, we still see housing making another significant (0.3 – 0.5 percentage points) contribution to GDP growth in 2013, as the positives driving the residential recovery more than outweigh the negatives.” Indeed, although the data are not final, housing contributed 0.3 percentage points to overall GDP growth in 2013. We expect housing to add between 0.2 and 0.3 percentage points to overall GDP growth in 2014.

At this stage of the recovery, satisfying pent-up demand for housing rather than mortgage rates will likely be the bigger driver of housing. Later on, when the pent-up demand is sated, interest rates (and affordability) should be key drivers, along with housing supply and demand, the willingness of banks and financial institutions to make mortgage loans, the health of the labor market, and the housing PE (median sales price/disposable median income per capita).

Although we continue to hear and read comments from housing market “bears” that the housing market is already back in a “bubble,” housing (represented by residential investment) currently accounts for just 3% of GDP. This is half of what it was at the peak of the housing market in 2005 – 06, when housing accounted for more than 6% of GDP. Since 1980, housing, on average, has accounted for 5% of GDP. At just 3% today, housing’s share of GDP is not only half of the recent peak, but also well below the long-term average of 5%. But what about the other housing indicators?

Key Housing Indicators

Many, if not all, of the other housing indicators we watch (see below) also suggest ongoing recovery in the housing market in the quarters and years to come.

To be sure, while the sharp increase in mortgage rates since mid-May 2013 may have slowed the pace of gains in the U.S. housing market, our view remains that the housing market is still in the early stages of recovering from the 2006 – 09 bust that followed the decade-and-a-half (early 1990s through mid-2000s) housing boom that began to show severe cracks in 2007 and collapsed in 2008. The collapse in housing, in turn, was a major contributor to the financial crisis and the Great Recession of 2007 – 09. The housing market, along with many financial markets and global economies, is still feeling the after-effects of the housing collapse.

The health of the housing market can be measured in many direct ways (e.g., housing starts, housing sales, construction spending, home prices) and indirect ways (e.g., homebuilder sentiment, mortgage applications, foreclosures, inventories of unsold homes, mortgage rates, housing vacancies, lumber prices, prices of publicly traded homebuilders). The U.S. government and private sources collect and disseminate these data. A quick recap of some of these indicators is below.

Taking the Pulse of the Residential Recovery

-

Near-record housing affordability. Housing affordability, the ability of a household with the median income to afford the payments on a median priced house at prevailing mortgage rates, hit an all-time high in early 2013 before the big run-up in mortgage rates that began in mid-May 2013. The latest data point (December 2013) saw a 21% drop in affordability from the peak in January 2013. Despite the drop, affordability remains well above the long-term average, and it is some 70% higher than at the peak of the housing market in late 2005/early 2006. Rising incomes and the aftermath of the 20 – 30% drop in home prices nationwide between 2005 and 2009 will continue to support an elevated level of affordability. At this point in the housing recovery, pent-up demand will likely outweigh affordability as the main driver of housing demand.

-

The housing PE. Although not a perfect measure of the frothiness (or lack thereof) in the housing market, the ratio of the median sales price of an existing home ($197,700 in December 2013) to disposable personal income per capita ($39,726 as of December 2013) is one way to gauge the health of the market. Our infographic shows that while the housing PE”has moved higher in recent months, it remains well below average. Indeed, aside from the housing bust era (2007 – 11), the housing PE is the lowest it has been in more than four decades. This also suggests that the housing recovery remains in its early stages and is not in a bubble.

-

Inventories of unsold homes are tight. Although the inventory of unsold new and existing homes has moved up from a 32-year low since the start of 2013, inventories of unsold homes remain well below average. The official count of the inventory of unsold single-family existing homes (from the National Association of Realtors), along with the record-low inventory of new homes for sale, tells us 1.8 million homes are for sale. Depending on the data source cited (there is no “official” number for shadow inventory), the shadow inventory is in the 1.0 – 1.5 million range. The low inventory of unsold homes, particularly in areas where housing demand is the highest, supports ongoing improvement in housing construction and housing sales.

-

Supply of home mortgages. From the mid-1990s through late 2006, bank lending standards (down payment required, credit scores, work history, etc.) for residential mortgages were relatively easy. Coupled with low rates and rapid innovation in financial products backing residential mortgages, this easy credit helped to fuel the housing boom. The banking industry began tightening lending standards in early 2007, and continued to tighten for more than two years. Lending standards eased in 2009 and 2010, but remained more restrictive than they were in the peak boom years from 2004 to 2006. The latest survey (February 2014) reveals that bank lending standards for home mortgages are now back to “normal,” as defined by the 10 years between 1995 and 2005. It’s too soon to tell whether or not the tightening of standards in the latest period (February 2014) is the start of a new trend, or just a wiggle in the data. Either way, relatively normal mortgage lending standards are supportive of more gains in housing in the coming quarters. The Federal Reserve (Fed) compiles these data in the quarterly Senior Loan Officer Survey.

-

Demand for home mortgages. Consumer demand for mortgages remained muted during the first two-and-a-half years (early 2009 through late 2011) of the housing recovery, as consumers remained uncertain about prospects for home price appreciation and their own financial and labor market status. Between mid-2011 and mid-2013, an improving labor market, Fed actions to lower mortgage rates, and rising home prices drove consumer demand for mortgages to levels not seen since the early 2000s. But the rise in mortgage rates since mid-2013 has had a meaningful impact on demand for mortgage loans in recent quarters, and a further pullback in consumer demand for mortgages would be a threat to the sustainability of the recovery. The housing recovery is dependent upon low interest rates, but not necessarily the lowest interest rates. History shows us that if job and income growth can rise along with mortgage rates, the growth in housing can continue. The Fed compiles these data in the quarterly Senior Loan Officer Survey.

-

Demand for housing. Net household formation boomed in the mid- 2000s (2004, 2005, and 2006) but began to slow just prior to the start of the Great Recession in 2007. Unemployed new graduates were living with their parents or renting in large groups rather than moving into homes of their own for years after the 2007 – 09 recession. But that is ending. Over the past five years, (2009 – 13) household formations have stabilized, partially due to the better labor market, but also thanks to the echo boomers reaching their mid-to-late 20s. Although new household formation has slowed from its pre-Great Recession pace, it is still running at almost 1.0% per year. By early 2011, the gap between new household formation and new housing starts had never been wider. Soon thereafter, housing starts began to recover, and the healing in the housing market began to accelerate. However, there are still more than 18 million vacant homes — down from the peak of more than 19 million, but still well above the pre-Great Recession level of 14 – 15 million. This indicator continues to suggest that the housing recovery is still in its early stages. The U.S. Census Bureau collects the data on household formation and housing vacancies.

On balance, the sharp rise in mortgage rates that commenced in mid- May 2013 will likely slow the pace of housing activity that had accelerated noticeably between mid-2011 and mid-2013. Despite the rise in rates, most of the indicators we watch suggest that the housing recovery remains firmly entrenched. The pace (and sustainability) of the housing recovery will help to determine the pace of the overall economic recovery. We expect housing — as measured by the residential investment component of GDP — to make a positive contribution to overall GDP growth in 2014, as it did in both 2012 and 2013. However, it will likely take several more years before the national housing market is back to normal.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments and exports less imports that occur within a defined territory.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC

Health Care Checkup

October 1, 2013

What We Spend on Health Care

This week, health care is likely to be in the news as a key component of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA). Enrollment for individuals seeking insurance coverage takes effect on October 1, as members of Congress continue to debate the merits (and funding) of the law as part of the discussion around providing funding for the federal government. We’ll leave the pros and cons of the ACA to the politicians and pundits and focus instead on the size and scope of the health care sector in the U.S. economy. In future Weekly Economic Commentaries, we’ll explore the impact of health care on the labor market, various segments of the economy, the federal budget, inflation, and the impact of demographics on health care spending. On balance, how we (as individuals and as an economy) consume, pay for, and manage the cost of health care will play a crucial role not only in the economy, but in the federal budget in the years and decades to come.

How We’re Covered

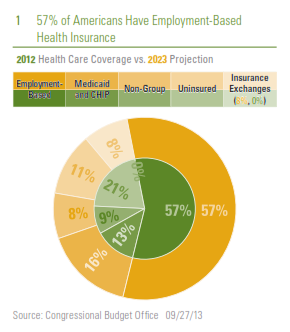

Most, though not all, of the spending patterns discussed below are driven by what type of health insurance, if any, individuals have. Using data compiled by the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which assigns people to their primary source of insurance (many people have multiple sources of insurance, especially those eligible for Medicare who also purchase additional insurance), we find that 156 million people (or 57% of the non-elderly population) have employment-based health insurance. By 2023, the CBO projects that this figure will increase to 162 million but will remain at 57% of the non-elderly population. At 57 million, or 21% of the non-elderly population, the uninsured made up the second-largest portion of the population in 2012. The CBO projects that under current law, the number of uninsured will drop to 31 million or 11% of the non-elderly population by 2023. More people are likely to move onto Medicaid and to the government-run health insurance exchanges as prescribed by the ACA while those purchasing non-group insurance will remain roughly steady at 8% of the non-elderly population. This potential shift in how Americans purchase health insurance has major implications for the overall economy and the outlook for the budget, which we’ll discuss in depth in future editions of the Weekly Economic Commentary.

How We Spend Our Health Care Dollars

Economy-wide (federal, state, and local governments, corporations, and individuals), Americans spent $2.7 trillion (or roughly 18% of gross domestic product [GDP]) on health care products, services, and investment in 2011, the latest data available.

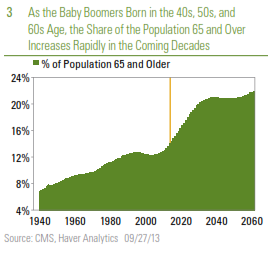

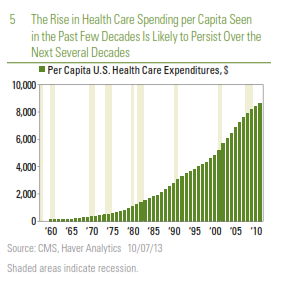

To put that in perspective, only three countries, China, Japan, and Germany, have economies larger than $2.7 trillion. Ten years ago, the figure was closer to 15% of GDP, and 30 years ago (1982) health care represented less than 10% of GDP. The rise in the percentage of the economy accounted for by health care is because spending on health care has risen much faster than GDP. Over the last 10 years, for example, health care spending has increased at a 5.5% annualized rate while overall GDP has increased at only a 4.0% pace. Although the aging population has played a role in this increase, and will continue to for many decades to come, health care spending per capita has increased 5% per year over the past 10 years to nearly $9,000, suggesting that even without the demographic shift, we are spending more on health care than ever before.

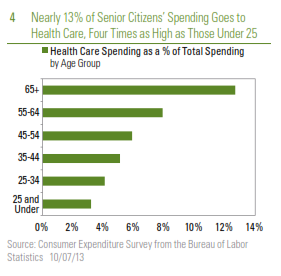

Of the $2.7 trillion spent economy-wide on health care in 2011, about one-third is on hospital services, another 25% is on professional services (doctors, dentists, clinics), and 15% is on medical products, including pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, and medical supplies. $308 billion is spent by individuals out of pocket on health care, more than is spent by individuals on new passenger cars and light trucks (approximately $240 billion in 2012), furniture and appliances (~$275 billion), or clothing (~$290 billion). Health insurance pays for another $2 trillion in health care expenses. Private insurance covers $900 billion of that $2 trillion, Medicare insurance for the elderly covers $550 billion, and Medicaid insurance for the poor covers $400 billion. The surprise here is that out-of-pocket expenses (~$300 billion) as a percent of total health care expenditures ($2.7 trillion) are just 11%, and have been moving lower for more than five decades.

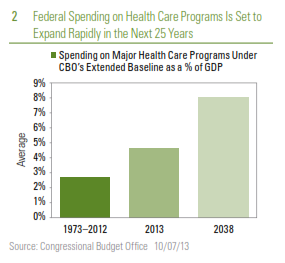

As noted above, we’ll discuss the impact of health care spending on the federal budget in a future edition of the Weekly Economic Commentary, but it’s important to note that the portion of health care spending economywide “sponsored” by governments has risen steadily over the past 25 years and is projected to continue to increase over the next 10 years and beyond, as the population ages and more people move into Medicare.

Allocation of Health Care Dollars Shifting Toward Government

In 1987, 68% of health care spending was initiated by the private sector (private businesses, households, and health-related philanthropic organizations), with one-third coming from businesses and roughly twothirds from households. Within the private sector, the ratio between businesses (one-third) and household spending (two-thirds) has remained relatively steady over the past 25 years. In 2012, just 55% of health care spending was initiated by the private sector, down from 68% in 1987, while government (federal, state, and local) accounted for 45%, up from 32% in 1987. This trend is expected to rise over the next 10 years.

Business spending in this context includes:

Household spending on health care includes:

Shifts in the mix of spending by businesses and consumers on various aspects of health care will continue to impact the economy for many years to come, and hopefully inform policy choices about who pays and how much is paid for health care in the coming decades.

Because the U.S. government is paying an ever-increasing share of health care costs, and more businesses and individuals are paying less out of pocket for health care, the actual cost and quality of health care is not as transparent as it should be. For example, we are likely to know far more about the cost and quality of the house we’re going to buy, the car we’re going to lease, and the vacation we’re going to take than we often do about our health care purchases. The overall cost of health care, combined with the lack of transparency throughout the system, will likely remain ongoing concerns for health care policymakers in the coming years and decades.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Stock investing involves risk including loss of principal.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments and exports less imports that occur within a defined territory.

The Congressional Budget Office is a non-partisan arm of Congress, established in 1974, to provide Congress with non-partisan scoring of budget proposals.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC

Posted in Affordable Care Act, China, Congressional Budget Office (CBO), GDP - Gross Domestic Product, Germany, Health Care, Healthcare cost, Hospital Cost, Insurance, Japan, Medicaid, Medicare, Weekly Economic Commentary | Tagged: Affordable Care Act, CBO, China, Congress, GDP, Germany, healthcare, Healthcare costs, Hospital costs, insurance, Medical, Weekly Economic Commentary | Leave a Comment »