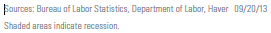

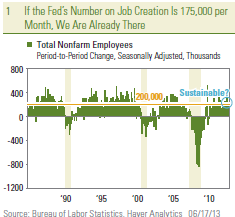

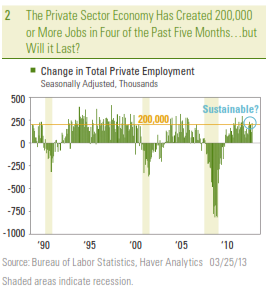

This Friday, March 7, 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor will release the Employment Situation report for February 2014. The Employment Situation report is two reports in one; the household survey generates the headline unemployment rate, while the establishment survey generates the nonfarm payroll job count. The unusually harsh winter weather across a large swath of the nation in February 2014 will likely have a major impact on the employment data in February. As of early Monday, March 3, 2014, the consensus of economists as polled by Bloomberg News is looking for a net increase of 154,000 private sector jobs in February 2014, after the 142,000 gain in January 2014. Prior to the 75,000 weather-impacted gain in jobs in December 2013, the private sector economy was consistently creating between 175,000 and 200,000 net new jobs per month. We continue to look for a return to that pace of job creation once the weather returns to normal.

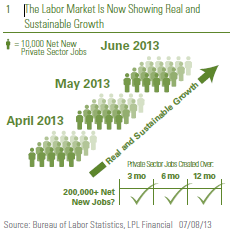

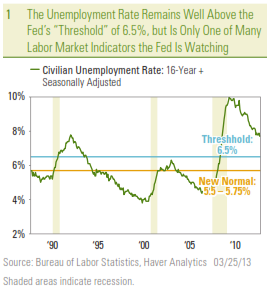

The consensus is looking for a 6.6% reading on the unemployment rate (see “A Closer Look: Labor Market Surveys,” page 5) in February 2014, the same reading as in January 2014. The market will be especially interested in the unemployment rate this month because just a 0.1% drop to 6.5% pushes the rate to the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) threshold of 6.5%.

This threshold was a common theme in the second leg of Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s testimony before the Senate Banking Committee late last week (Thursday, February 27, 2014). Although the focus in the media this week ahead of the release of the Employment Situation report is likely to be on the nonfarm payroll job count and the unemployment rate, in this week’s Weekly Economic Commentary, we will focus on Janet Yellen’s employment report on various employment statistics that Yellen said the Fed will be watching closely.

Last week, senators on the Senate Banking Committee asked Yellen several times about the state of the labor market. A sampling of her answers is below, and we’ve bolded some of the labor market metrics she mentioned:

The unemployment rate is not a sufficient statistic to measure the health of the labor market. An additional 5 percent, an unusually high fraction of our labor force is working part time for economic reasons which means they’re unable to get full-time work but want it. That’s an additional 7 million plus Americans who are involuntarily employed part time. And we have [an] unusually high fraction of Americans who are unemployed and have been for substantial amounts of time. So, you know, as we go — go to a fuller consideration of how is the labor market performing, we need to take all of those things into account.

There is no hard and fast rule about what unemployment rate constitutes full employment, and we need to consider a broad range of indicators. Many members of the committee have emphasized this point and it’s one I agree with.

Well, Senator, we are very focused on and concerned about the high level of long-term unemployment. It’s really unprecedented to see something like 37 percent of unemployed in long spells. I mean, what can we do? We can try to foster a stronger labor market generally. We don’t have tools that are targeted at long-term unemployment. But in taking account of how much slack there is in the labor market…

Look, if the unemployment rate is above that (6.5%), we see absolutely no need to consider any possibility of raising rates. Below that we begin to look more carefully.

The unemployment rate, if I had to choose one metric, the unemployment rate is probably best. And members of our committee aren’t certain exactly what constitutes full employment, but generally see a range of 5 percent to 6 percent or a little bit in that area to be a state of full unemployment in the economy. But also looking at part time employment, job flows, what’s happening with wages and a broader set of metrics I think is necessary.

The fact that we’ve seen very slow growth in wages, for example, I take as one of many pieces of information suggesting the labor market has not — has not returned to normal and has quite a ways to go.

Fed Monitoring Labor Market Indicators

In general, Yellen made it clear that the Fed is in no hurry to raise rates when the unemployment rate crosses the 6.5% threshold. This metric was first cited by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) in December 2012, when it noted that it “currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.”

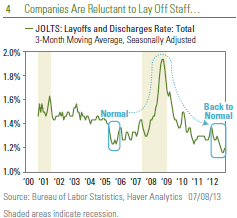

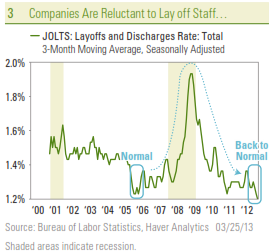

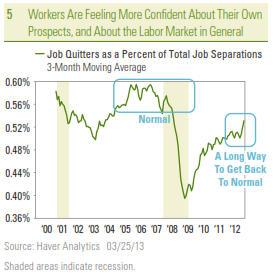

Instead, Yellen pointed out, the Fed would broaden the labor market indicators it is monitoring, and “look more carefully” at other relevant metrics. The tone of Yellen’s remarks indicated that while she didn’t speak for the FOMC, she was not ready to say that the labor market was back to normal, or anywhere close to it, even though the unemployment rate was poised to cross the 6.5% threshold.

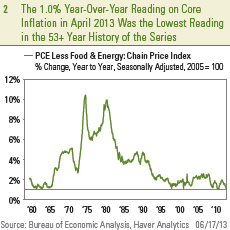

The risk in this view for financial markets — and especially the bond market — is that there is less slack in the labor market than Yellen and most other members of the FOMC think there is. While there are still many more factors pushing down on inflation than pushing inflation higher, wages account for two-thirds of businesses’ costs, and therefore, play a big role in the overall pace of inflation. We have already seen evidence that wages are rising and labor market conditions are tightening in a few scattered industries. For example, energy, construction, information technology, and logistics were cited in the most recent Beige Book as professions that were seeing above-average wage increases and higher starting pay for skilled workers. We are likely to hear more about this in the next Beige Book, which is due out this week. If market participants sense that wage pressures are gaining momentum, and that the Fed is “behind the curve” on inflation, bond yields could rise rapidly over a short period of time and counteract the monetary stimulus the Fed is supplying to the economy.

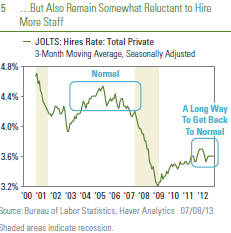

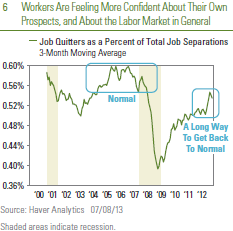

The infographic on page 4 details the performance of nine key labor market metrics mentioned by Yellen in her recent public appearances. Although most have partially recovered from their Great Recession nadirs, only a few have returned to “normal.” Until they do — or at least until they make significant progress toward normal — markets should expect that the Fed will be content with keeping its fed funds rate target near zero. In our view, late 2015 or even early 2016 is when the Fed is likely to begin raising rates.

A Closer Look: Labor Market Surveys

- A survey of 60,000 households nationwide — an incredibly large sample size for a national survey — generates the data set used to calculate the unemployment rate, the size of the labor force, part-time and full-time employment, the reasons for and duration of unemployment, and employment status by age, educational attainment, and race. The “household survey” has been conducted essentially the same way since 1940, and although it has been “modified” over the years, the basic framework of the data set has stayed the same. The last major modification to the data set (and to how the data is collected) came in 1994. To put a sample size of 60,000 households into perspective, nationwide polling firms typically poll around 1,000 people for their opinion on presidential races.

- The headline unemployment rate (6.6% in January 2014) is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed (10.2 million in January 2014) by the number of people in the labor force (155.5 million). The civilian population over the age of 16 stood at 246.9 million in January 2014. A person is identified as being part of the labor force if they are over 16, have a job (employed), or do not have a job (unemployed) but are actively looking for work. A person is not in the labor force if they are neither employed nor unemployed. This category includes retired persons, students, those taking care of children or other family members, and others who are neither working nor seeking work.

- In January 2014, the labor force was 155.5 million, which consisted of 145.2 million employed people and 10.2 million unemployed people. Another 91.4 million people over the age of 16 were classified as not in the labor force. The 155.5 million people in the labor force plus the 91.4 million people not in the labor force is equal to the over 16 civilian population, 246.9 million.

- The payroll job count data are culled from a survey of 440,000 business establishments across the country. The sample includes about 141,000 businesses and government agencies, which covers approximately 486,000 individual worksites drawn from a sampling frame of Unemployment Insurance (UI) tax accounts covering roughly 9 million establishments. The sample includes approximately one-third of all nonfarm payroll employees. From these data, a large number of employment, hours, and earnings series in considerable industry and geographic detail are prepared and published each month.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Stock investing involves risk including loss of principal.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics is a government agency that produces economic data that reflects the state of the U.S. economy. This data includes the Consumer Price Index, the unemployment rate and the Producer Price Index.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC