In this week’s commentary we attempt to clear up some of the confusion around some of the most common questions we encounter regularly, including:

- The Federal Reserve (Fed), its balance sheet, its role in the economy,and its impact on inflation;

- The federal budget deficit;

- The federal debt outstanding, and the debt-to-GDP ratio; and

- The trade deficit and a related topic, the US dollar.

In many ways, the items above are related. But oftentimes, pundits, politicians, newsletter writers, bloggers, Tweeters, and even the “traditional media” will confuse or conflate one or more of these issues, and that’s usually when we get a call about it in the LPL Financial Research Department.

The Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve (Fed) was created in 1913 by an act of Congress, The Federal Reserve Act, to provide “the nation with a safer, more flexible, and more stable monetary and financial system.” The Fed was created after a series of financial panics, bank runs, credit crunches, and booms and busts in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Over time, the Fed’s role in the economy has expanded, and currently, the Fed has a “dual mandate” from Congress (via the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1978) to conduct monetary policy that aims to promote “full employment and reasonable price stability.” In plain English, Congress created the Fed to run monetary policy, and could, at any time, vote to take away or modify the Fed’s dual mandate. In fact, Congress could run monetary policy themselves if they voted to do so, although it would be an understatement to say that markets would not embrace that outcome were it occur.

As part of its mandate from Congress, the Fed’s policymaking arm, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) can raise or lower the interest rate banks charge each other for overnight loans, and expand and contract its balance sheet (quantitative easing, or QE) to achieve its goals. Since 2008, the Fed has pursued several rounds of QE — the purchase of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in the marketplace — by creating “reserve credits.” The Fed’s balance sheet currently stands at just over $3 trillion, and it is likely to continue to grow over the remainder of 2013 and perhaps beyond.

The Fed’s balance sheet does not add to the federal deficit (see below), nor does the Fed set interest rates in the marketplace — beyond interest rates on overnight lending. Interest rates on everything from 3-month T-bills to 30-year Treasury bonds are set by the market, not the Fed. While the Fed is not responsible for fiscal policy or the budget deficit (see below), an argument has been made that the Fed is encouraging fiscal policymakers to overspend by buying the debt issued by the Treasury to fund the spending. In all likelihood however, Congress would be spending more than it takes in, and the Treasury would be issuing the debt to fund this overspending anyway. The difference is that instead of the Fed buying the Treasuries, other entities (the U.S. public, bond funds, pension funds, insurance companies, foreign entities, etc.) would be buying the debt, albeit at a slightly higher yield, and a slightly higher cost to the Treasury.

Our view remains that the Fed will continue its program of QE over the remainder of 2013, and keep rates at or near zero until at least 2015.

The risk of inflation from the Fed’s policies would arise if all the money the Fed is pumping into the system (mainly onto commercial banks’ balance sheets) would be lent out all at once by those banks to businesses and consumers across the country and around the world. While there has been some lending, lending activity has not been robust, and indeed the velocity of money — the rate at which money sloshes around in the economy — has fallen by a third since the onset of the financial crisis in 2007 – 08, and shows no signs of reversing. (Please see the Weekly Economic Commentary: (Inflation Situation Revisited from March 18, 2013 for more on our view on inflation).

In short, the Fed runs monetary policy and is given that mandate by Congress. Our view remains that the Fed will continue its program of QE over the remainder of 2013, and will keep rates at or near zero until at least 2015.

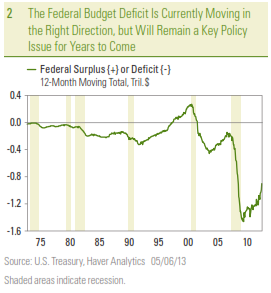

Federal Budget Deficit

The federal budget deficit is the difference between what the Treasury collects in taxes (personal income taxes, payroll taxes, excise taxes, corporate taxes) and fees, less what the federal government spends (on defense, social programs, roads, education, etc.). Deficits increase when the federal government, authorized by Congress, spends more than it takes in, and deficits decrease when the federal government takes in more revenue than it spends in a year. A large percentage of federal spending is set on autopilot via mandatory spending on programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid (see the Weekly Economic Commentary from October 29, 2012), although smaller portions of the budget (interest payments on the federal debt and spending on non-mandatory items) are determined by Congress annually.

Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy (decisions on how the government should raise revenue and/or manage spending) is made by Congress, with the President having veto power over what Congress decides. The federal budget deficit (in dollar terms and as a percent of gross domestic product [GDP]), is headed lower, at least over the medium term, helped by tax increases, the sequester spending cuts, the fading impact of the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, and the improving economy, leading to higher revenues and lower spending for items such as unemployment insurance. While this improvement in the overall budget picture is welcome, and somewhat of a surprise to many, it may lead to complacency, and prevent the policymakers responsible for fiscal policy from taking the needed actions to begin to address our longer-term budget problems. While the Fed has no role in setting fiscal policy, the Fed’s own policies do impact the deficit. The Fed’s operations historically earn a profit, as the revenue it takes in via open market operations as well as by check and electronic payments processing for the financial system, far exceed its operating costs. The Fed promptly returns all profits back to the Treasury. In 2012, the Fed paid $88 billion into the Treasury, and it has consistently returned profits to the Treasury since the mid-1930s. The Fed’s monetary policy can also impact what the federal government pays in interest on the public debt. By keeping short-term rates low, the Fed is helping to keep interest payments owed by the federal government low. By keeping a lid on inflation, the Fed has a hand in keeping intermediate- and long-term interest rates low, which in turn helps to keep the interest paid by the federal government on intermediate- and longer-dated Treasuries low.

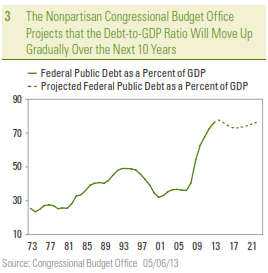

Federal Debt

The federal debt is simply the federal deficit accumulated over the years. When the deficit increases in a given year because the federal government spends more than it takes in, the debt increases. There are several measures of federal debt, the broadest being total public debt outstanding, which was $16.8 trillion at the end of March 2013. Of that, $11.9 trillion was marketable and held by the public (and half of that is held by foreigners), while $4.9 trillion is owned by entities within the federal government. The debt-to-GDP ratio is calculated by dividing the debt (total, held by public, etc.) by nominal GDP (See the Weekly Economic Commentary: The ABCs of GDP from May 6, 2013), which stands at $16 trillion. So the United States’ debt-to-GDP ratio measured by total debt outstanding ($16.8 trillion) divided by nominal GDP ($16 trillion) is 105%. However, most market participants exclude the federal debt owed to other federal government entities and calculate the debt-to-GDP ratio as debt owned by the public ($11.9 trillion) divided by nominal GDP ($16.0) trillion for a debt-to-GDP ratio of just over 74%. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projects that public debt outstanding as a percent of GDP (currently at 74% of GDP) will rise gradually to 77% of GDP by 2023, assuming current law and trend-like 2.8% real GDP growth over the next 10 years.

The structural and demographic problems that will drive the deficit over the next several decades remain in place, and the longer policymakers wait to address the problems, the more difficult (and painful) it becomes to address the problems later on.

The real problem posed by the federal debt, however, is the structural deficits in the Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid programs, which won’t be helped much by an improving economy. The biggest risk on the federal debt is that the recent improvement in the deficit (and relative stability in the debt-to-GDP ratio) allows complacency to set in among policymakers in Washington. The structural and demographic problems that will drive the deficit over the next several decades remain in place, and the longer policymakers wait to address the problems, the more difficult (and painful) it becomes to address the problems later on.

Trade Deficit

The difference between what we export in goods and services to other countries, and what we import in goods and services from other countries is our trade deficit. Many factors influence the trade deficit, including, but not limited to:

- The value of the dollar;

- The relative strength of our economy to economies outside the United States;

- The quality of goods and services made here relative to the quality of the goods and services created overseas; and

- Trade barriers and tariffs.

The United States is still likely to run a substantial trade deficit in the years ahead, and the trade sector will continue to weigh on overall GDP growth and the value of the dollar.

We currently run a very large deficit on goods (importing $2.3 trillion and exporting just $1.6 trillion over the past 12 months), but we run a small net trade surplus (importing $435 billion and exporting $636 billion) on the service side. Congress and the President can impact trade directly (via trade agreements, tariffs) and indirectly (via enacting industry and product-specific tax and regulatory measures). A nation’s fiscal policy can have an influence on the trade deficit as well, if the fiscal policy impacts economic growth, the value of the dollar, etc. The Fed’s main impact on the trade deficit is via interest rates and the dollar. Typically, if the Fed is cutting interest rates or maintaining “easy” monetary policy, the dollar may decline in response, making our exports less expensive to the rest of the world. The nascent revival of the U.S. manufacturing sector along with the now ample supply of natural gas and related products will help to hold the trade deficit in check by reducing our dependence on foreign manufactured goods and imported energy and energy products. Despite these positives however, the United States is still likely to run a substantial trade deficit in the years ahead, and the trade sector will continue to weigh on overall GDP growth and the value of the dollar.

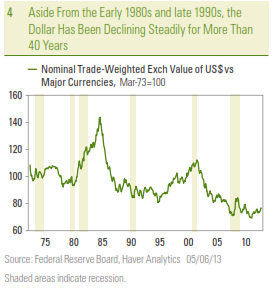

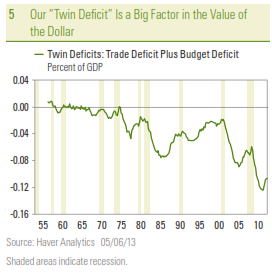

The Dollar

Aside from two periods in the early 1980s and late 1990s, the US dollar has been declining since it went off the gold standard in the early 1970s. The value of the dollar is set in the open market, although the Fed, Congress, and the President can have an impact on the dollar. Of the three, the Fed probably has the most direct impact on the value of the dollar, as it sets short-term interest rates, which often have a big influence on the value of a nation’s currency. The Fed’s current program of QE is increasing the number of dollars in the world, and helping to put downward pressure on the dollar. Trade policy, broad economic policy, and even foreign policy — set by Congress and/or the President — can also impact the value of the dollar. Our “twin deficits” (trade and budget) have put downward pressure on the dollar over the past several decades, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

Since the United States is the world’s largest economy, most global trade is denominated in dollars, making the dollar the world’s “reserve currency.” Central banks and governments of most nations outside the United States hold reserves in dollars, although the rise of China’s economy and the sheer size of the Eurozone’s economy has eroded the dollar’s “reserve currency” status in recent years. Still, the dollar is still viewed as a “safe haven,” and in times of economic and political uncertainty around the globe, the dollar normally rises in value.

While our “twin deficits” and the Fed’s actions to stimulate the economy are putting downward pressure on the dollar, the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency, and the United States’ position as the world’s largest economy and the world’s largest exporter with a diversified and dynamic economy and labor force, suggests that a sudden, sharp decline in the value of the dollar is unlikely. We continue to believe the dollar will slowly depreciate over time — continuing the trend that has been in place since the early 1970s.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly. Gross domestic product (GDP) is the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within

a country’s borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments and exports less imports that occur within a defined territory.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Stock investing involves risk including loss of principal.

Quantitative easing is a government monetary policy occasionally used to increase the money supply by buying government securities or other securities from the market. Quantitative easing increases the money supply by flooding financial institutions with capital in an effort to promote increased lending and liquidity.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) , a committee within the Federal Reserve System, is charged under the United States law with overseeing the nation’s open market operations (i.e., the Fed’s buying and selling of U.S. Treasury securities).

The Congressional Budget Office is a non-partisan arm of Congress, established in 1974, to provide Congress with non-partisan scoring of budget proposals.

Government bonds and Treasury Bills are guaranteed by the U.S. government as to the timely payment of principal and interest and, if held to maturity, offer a fixed rate of return and fixed principal value. However, the value of fund shares is not guaranteed and will fluctuate.

Mortgage-Backed Securities are subject to credit, default risk, prepayment risk that acts much like call risk when you get your principal back sooner than the stated maturity, extension risk, the opposite of prepayment risk, and interest rate risk.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

INDEX DESCRIPTIONS

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services.

Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) is an indicator of the economic health of the manufacturing sector. The PMI index is based on five major indicators: new orders, inventory levels, production, supplier deliveries and the employment environment.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is

not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit