Exploring the Disconnect

What are the reasons for the apparent disconnect between reported inflation and what consumers and businesses see at gas stations, the mall, the grocery store, and elsewhere? The Consumer Price Index (CPI), the Personal Consumption Expenditures deflator (PCE), and other inflation indices tell one story, whereas consumers and businesses tell another. We will explore this question in today’s commentary.

We began this discussion last week, when we wrote about how the conversations most consumers and small businesses are having about higher prices for food, energy, and other items like education and medical services, are at odds with policymakers’ and the markets’ views on inflation.

Although there are likely many reasons for the disconnect in the inflation conversation, we believe most of it can be explained by the following factors:

- Definitions;

- Quality;

- Frequency;

- Weighting;

- Age;

- Geography; and

- Substitutability.

Of course, not all of the differences in what consumers and businesses see and hear about higher prices can be attributed to the above factors. We examine the quality and definitional issues in depth in this week’s report, and will return to the other factors at a later date.

Definitions Disconnect

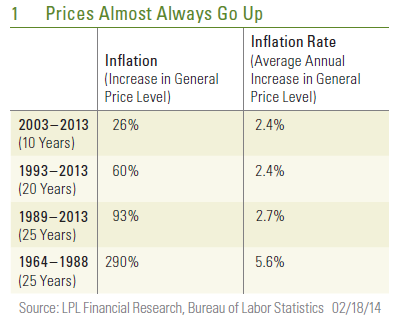

By definition, inflation is a sustained, broad-based increase in the general level of prices, but we often hear from policymakers that “there is no inflation.” According to the CPI, the general price level has increased by 26% over the past 10 years, 60% over the past 20 years, and 93% over the past 25 years. To put it another way, the general price level has nearly doubled in the past 25 years (since 1989). When policymakers say there is “no inflation” or that inflation is “well contained,” they are generally talking about the rate of increase of inflation.

Over the past 10 years, the 26% increase in the general price level works out to a 2.4% annualized increase in inflation per year. The 60% increase in the general price level over the past 20 years is also equivalent to a 2.4% annualized increase in inflation per year. The 93% gain in the general price level over the past 25 years (1989 – 2013) works out to a 2.7% gain per year in inflation in each of those 25 years.

So, in general, when policymakers say there is no inflation, they do not mean that prices are not going up. Prices almost always go up. What they mean is that the rate of change in the general price level, or the inflation rate, is moderate. By comparison, in the 25 years ending in 1988, the general price level increased by 290%, and the average annual rate of change in the CPI was 5.6% per year, more than double the rate observed over the 1989 – 2013 period [Figure 1].

Quality Disconnect

In 1990, the best-selling car in America was the Honda Accord. It had power brakes, power steering, and a five-speed manual transmission. Air conditioning and AM/FM cassette stereo system were optional, and it got 21 miles per gallon (MPG) around town and 27 MPG on the highway. The manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) was $12,145.

The top-selling car in 2013 was the Toyota Camry. It also had power brakes and power steering. But air conditioning and the AM/FM stereo came standard, and it had an automatic transmission and got 25 MPG around town and 35 MPG on the highway. The 2013 Camry also came standard with:

-

A trip computer;

-

Cruise control;

-

Free maintenance for two years or 250,000 miles;

-

Free roadside assistance for two years or 25,000 miles;

-

A USB connection;

-

CD/MP3 player;

-

Bluetooth wireless;

-

Four-wheel anti-lock brakes;

-

Dual front and dual rear side-mounted airbags;

-

Traction control;

-

Daytime running lights;

-

Stability control;

-

Rear door safety locks;

-

Passenger airbag occupant sensing deactivation;

-

Intermittent wipers; and

-

VIP security system.

The MSRP for this car was $22,325, nearly double the price of the best-selling car in 1990 (the Honda Accord).

According to the New Vehicle Index within the CPI, new car prices increased by only 20% between 1990 and 2013. As noted above, the price of the top-selling car in 2013 was 84% higher than (nearly double) the price of the top-selling car in 1990. Why the disconnect [Figure 2]?

The disconnect comes in the quality adjustment that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) uses to make an “apples-to-apples” comparison of the 1990 Accord and the 2013 Camry. The quality adjustment attempts to account for the fact that the 2013 Camry had many more “bells and whistles” than the 1990 Accord. The quality adjustment does not only apply to cars. A large portion of the components of the CPI have some form of quality adjustment applied to the raw prices, and the level of quality adjustment applied varies from item to item. In many cases, it’s not possible to attribute how much of the change in the CPI for a particular component is due to the quality adjustment and how much is due to the increase in the raw price. However, it is clear that this process of quality adjustment adds to the disconnect in the inflation conversation.

On balance, many factors contribute to the disconnect between what policymakers and economists say about inflation, and what consumers and businesses see and hear when they make purchases. We discussed two of the drivers of the disconnect here, but many others warrant further discussion. For policymakers like the Federal Reserve (Fed), the low rate of increase in the inflation rate expected by its policymaking arm, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), this year (1.5%) and next year (1.75%) suggests that inflation is in fact “well contained.” Further, this low rate suggests the Fed can be patient as it begins to remove the monetary stimulus put into place over the past six years.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

INDEX DESCRIPTIONS

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services.

Personal Consumption Expenditures is a measure of price changes in consumer goods and services. Personal consumption expenditures consist of the actual and imputed expenditures of households; the measure includes data pertaining to durables, non-durables and services. It is essentially a measure of goods and services targeted toward individuals and consumed by individuals.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC