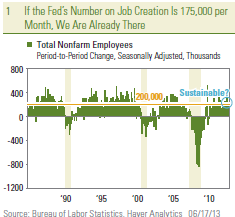

This Friday, March 7, 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor will release the Employment Situation report for February 2014. The Employment Situation report is two reports in one; the household survey generates the headline unemployment rate, while the establishment survey generates the nonfarm payroll job count. The unusually harsh winter weather across a large swath of the nation in February 2014 will likely have a major impact on the employment data in February. As of early Monday, March 3, 2014, the consensus of economists as polled by Bloomberg News is looking for a net increase of 154,000 private sector jobs in February 2014, after the 142,000 gain in January 2014. Prior to the 75,000 weather-impacted gain in jobs in December 2013, the private sector economy was consistently creating between 175,000 and 200,000 net new jobs per month. We continue to look for a return to that pace of job creation once the weather returns to normal.

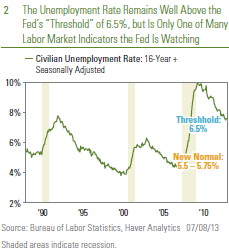

The consensus is looking for a 6.6% reading on the unemployment rate (see “A Closer Look: Labor Market Surveys,” page 5) in February 2014, the same reading as in January 2014. The market will be especially interested in the unemployment rate this month because just a 0.1% drop to 6.5% pushes the rate to the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) threshold of 6.5%.

This threshold was a common theme in the second leg of Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s testimony before the Senate Banking Committee late last week (Thursday, February 27, 2014). Although the focus in the media this week ahead of the release of the Employment Situation report is likely to be on the nonfarm payroll job count and the unemployment rate, in this week’s Weekly Economic Commentary, we will focus on Janet Yellen’s employment report on various employment statistics that Yellen said the Fed will be watching closely.

Last week, senators on the Senate Banking Committee asked Yellen several times about the state of the labor market. A sampling of her answers is below, and we’ve bolded some of the labor market metrics she mentioned:

The unemployment rate is not a sufficient statistic to measure the health of the labor market. An additional 5 percent, an unusually high fraction of our labor force is working part time for economic reasons which means they’re unable to get full-time work but want it. That’s an additional 7 million plus Americans who are involuntarily employed part time. And we have [an] unusually high fraction of Americans who are unemployed and have been for substantial amounts of time. So, you know, as we go — go to a fuller consideration of how is the labor market performing, we need to take all of those things into account.

There is no hard and fast rule about what unemployment rate constitutes full employment, and we need to consider a broad range of indicators. Many members of the committee have emphasized this point and it’s one I agree with.

Well, Senator, we are very focused on and concerned about the high level of long-term unemployment. It’s really unprecedented to see something like 37 percent of unemployed in long spells. I mean, what can we do? We can try to foster a stronger labor market generally. We don’t have tools that are targeted at long-term unemployment. But in taking account of how much slack there is in the labor market…

Look, if the unemployment rate is above that (6.5%), we see absolutely no need to consider any possibility of raising rates. Below that we begin to look more carefully.

The unemployment rate, if I had to choose one metric, the unemployment rate is probably best. And members of our committee aren’t certain exactly what constitutes full employment, but generally see a range of 5 percent to 6 percent or a little bit in that area to be a state of full unemployment in the economy. But also looking at part time employment, job flows, what’s happening with wages and a broader set of metrics I think is necessary.

The fact that we’ve seen very slow growth in wages, for example, I take as one of many pieces of information suggesting the labor market has not — has not returned to normal and has quite a ways to go.

Fed Monitoring Labor Market Indicators

In general, Yellen made it clear that the Fed is in no hurry to raise rates when the unemployment rate crosses the 6.5% threshold. This metric was first cited by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) in December 2012, when it noted that it “currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.”

Instead, Yellen pointed out, the Fed would broaden the labor market indicators it is monitoring, and “look more carefully” at other relevant metrics. The tone of Yellen’s remarks indicated that while she didn’t speak for the FOMC, she was not ready to say that the labor market was back to normal, or anywhere close to it, even though the unemployment rate was poised to cross the 6.5% threshold.

The risk in this view for financial markets — and especially the bond market — is that there is less slack in the labor market than Yellen and most other members of the FOMC think there is. While there are still many more factors pushing down on inflation than pushing inflation higher, wages account for two-thirds of businesses’ costs, and therefore, play a big role in the overall pace of inflation. We have already seen evidence that wages are rising and labor market conditions are tightening in a few scattered industries. For example, energy, construction, information technology, and logistics were cited in the most recent Beige Book as professions that were seeing above-average wage increases and higher starting pay for skilled workers. We are likely to hear more about this in the next Beige Book, which is due out this week. If market participants sense that wage pressures are gaining momentum, and that the Fed is “behind the curve” on inflation, bond yields could rise rapidly over a short period of time and counteract the monetary stimulus the Fed is supplying to the economy.

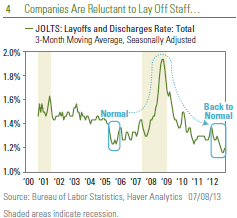

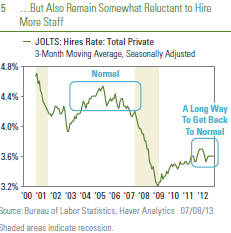

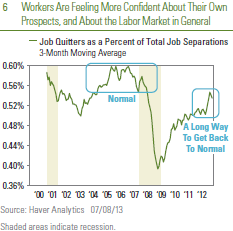

The infographic on page 4 details the performance of nine key labor market metrics mentioned by Yellen in her recent public appearances. Although most have partially recovered from their Great Recession nadirs, only a few have returned to “normal.” Until they do — or at least until they make significant progress toward normal — markets should expect that the Fed will be content with keeping its fed funds rate target near zero. In our view, late 2015 or even early 2016 is when the Fed is likely to begin raising rates.

A Closer Look: Labor Market Surveys

- A survey of 60,000 households nationwide — an incredibly large sample size for a national survey — generates the data set used to calculate the unemployment rate, the size of the labor force, part-time and full-time employment, the reasons for and duration of unemployment, and employment status by age, educational attainment, and race. The “household survey” has been conducted essentially the same way since 1940, and although it has been “modified” over the years, the basic framework of the data set has stayed the same. The last major modification to the data set (and to how the data is collected) came in 1994. To put a sample size of 60,000 households into perspective, nationwide polling firms typically poll around 1,000 people for their opinion on presidential races.

- The headline unemployment rate (6.6% in January 2014) is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed (10.2 million in January 2014) by the number of people in the labor force (155.5 million). The civilian population over the age of 16 stood at 246.9 million in January 2014. A person is identified as being part of the labor force if they are over 16, have a job (employed), or do not have a job (unemployed) but are actively looking for work. A person is not in the labor force if they are neither employed nor unemployed. This category includes retired persons, students, those taking care of children or other family members, and others who are neither working nor seeking work.

- In January 2014, the labor force was 155.5 million, which consisted of 145.2 million employed people and 10.2 million unemployed people. Another 91.4 million people over the age of 16 were classified as not in the labor force. The 155.5 million people in the labor force plus the 91.4 million people not in the labor force is equal to the over 16 civilian population, 246.9 million.

- The payroll job count data are culled from a survey of 440,000 business establishments across the country. The sample includes about 141,000 businesses and government agencies, which covers approximately 486,000 individual worksites drawn from a sampling frame of Unemployment Insurance (UI) tax accounts covering roughly 9 million establishments. The sample includes approximately one-third of all nonfarm payroll employees. From these data, a large number of employment, hours, and earnings series in considerable industry and geographic detail are prepared and published each month.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Stock investing involves risk including loss of principal.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics is a government agency that produces economic data that reflects the state of the U.S. economy. This data includes the Consumer Price Index, the unemployment rate and the Producer Price Index.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC

Trading Partners

September 3, 2013

The upward revision to second quarter gross domestic product (GDP) garnered a great deal of market attention last week (August 26 – 30, 2013). The report, released on Thursday, August 29, revealed that second quarter GDP — initially reported in late July 2013 as a 1.7% gain — was revised higher to a 2.5% gain. All of the upward revision to second quarter GDP can be explained by a narrower trade deficit. Initially, the trade deficit in the second quarter was reported as $451 billion, a 0.8% drag on overall GDP growth. Now, the revised data show that the trade gap stood at “only” 422 billion in the second quarter — the same as in the first quarter of 2013 — and as a result, the economic drag from trade for the quarter was eliminated. Looking ahead to the third quarter of 2013 and beyond, market participants and policymakers are asking: Can trade make a significant positive contribution to GDP growth in the quarters ahead, given the outlook for growth in Europe, China, Japan, and emerging markets?

Tracking the Pace of U.S. GDP Growth

While second quarter GDP was revised higher, the first quarter was not subject to revision and remained at 1.1%, leaving GDP growth in the first half of 2013 at a tepid 1.8%. The Federal Reserve (Fed) is still forecasting a 2.45% gain in GDP this year. With 1.8% growth in real GDP in the first half of the year, real GDP would have to grow by more than 3.0% in the third and fourth quarters of 2013 to match the Fed’s consensus forecast for the year. The Fed will release a revised forecast for the economy, labor markets, and inflation for 2013, 2014, and 2015 on September 18, 2013 at the conclusion of the next Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting. The FOMC is likely to revise downward its 2013 GDP growth forecast. The new forecast, along with the release of the FOMC’s initial public forecast for the economy, inflation, and the labor market in 2016 (also due on September 18), may help to soothe market fears about the pace of tapering and tightening.

The data in hand for the first two months of the third quarter of 2013 suggest that third quarter GDP is tracking to well under 2%, and may be closer to 1%. The data released thus far for the third quarter of 2013 include:

Data due out this week (September 2 – 6, 2013) on vehicle sales, the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), merchandise trade, construction spending, factory shipments and inventories for July and August 2013, and, of course, the August employment report (due out on Friday, September 6) will help to further clarify the pace of GDP growth in the current quarter, the rest of 2013, and into 2014.

GDP Overseas

Data released over the past several months suggest that the economies in Europe and China have stabilized. Meanwhile, market participants have increased their GDP growth forecasts for Japan over the past nine months, as Japanese policymakers have ramped up monetary and fiscal policy and embarked on a series of structural reforms aimed at jarring Japan’s economy out of a multi-decade slumber. Our view remains that while the economies in China and Europe have stopped getting worse, it may take several more quarters before they can meaningfully re-accelerate. While growth has picked up in Japan — second quarter GDP growth in Japan was 2.6% — it remains disappointing relative to elevated expectations. In addition, many emerging market nations (about 50% of U.S. exports head to emerging markets), including India, Brazil, and Indonesia are now experiencing growth and inflation scares, and some (Brazil and Indonesia) are raising interest rates to head off inflation. Many of the market participants and Fed policymakers who expect U.S. GDP to accelerate in the second half of 2013 and in 2014 are likely counting on accelerating growth in Europe, China, Japan, and emerging markets to drive U.S. exports higher. But is that enough to boost U.S. GDP growth?

As noted in our Weekly Economic Commentary: Exporting Good Old American Know-How, from August 19, 2013, the United States has run a trade deficit (importing more goods and services from other countries than it exports) since the mid-1970s, and our large deficit on the goods side (around $759 billion in 2012) more than offsets the trade surplus we have on the service side of the ledger (around $213 billion in 2012). Combined, our goods and services trade deficit was $547 billion in 2012, slightly smaller than the $569 billion deficit in 2011. As a result of the slight narrowing of the deficit between 2011 and 2012, net exports contributed 0.1% to the 2.8% gain in GDP in 2012.

Net Exports Typically Do Not Boost U.S. GDP Growth

The infographic on page 2, “Profile of U.S. Exports” (Profile) reveals that over the past 40 years — aside from recessions (when imports fall faster than exports, narrowing the trade deficit) — net exports have never added more than 1.0% to overall GDP growth. Thus, even if the economies of Europe, China, Japan, and emerging markets accelerate sharply in the next few quarters, it is unlikely that net exports will provide a large boost to GDP growth this year.

In theory, an unexpected uptick in economic activity among our largest export destinations should be a plus for our exports to that region, but in practice, the impact to our trade balance and economy may not immediately reflect the better growth prospects overseas. In addition, exchange rate movements also can influence cross-border trade, but movements often work with a long lag. Since many of our exports do not compete on price, the value of the dollar is not always the best way to gauge the relative strength of our exports to many markets. Generally speaking, U.S. exports compete globally on quality, rather than price.

Export Destinations: Economic Prospects in Canada and Mexico

The Profile details the destinations (trading partners) and mix (goods versus services) of our exports. Fourteen percent of our exports (both goods and services) are bound for the Eurozone, while just 6% head to China. Remarkably, only 5% of our exports go to Japan. Combined, our exports to the Eurozone, Japan, and China account for 25% of our total exports. Closer to home, 16% of our exports head north of the border to Canada, and another 11% head south of the border to Mexico. Thus, our exports to our two closest neighbors (27% of all exports) are larger than our exports to the Eurozone, Japan, and China combined (25%). Accordingly, market participants should probably pay more attention to the economic prospects of Canada and Mexico and a bit less to the prospects of China, the Eurozone, and Japan.

Mix of Goods/Services: Goods Are 70% of All Exports

The Profile also details the goods/services mix of our exports. Currently, goods account for around 70% of all exports, but that varies widely by trading partner. The export mix to Canada and Mexico is skewed toward goods rather than services, which is partially explained by auto production, since auto parts factories and final assembly plants account for such a large portion of trade. Our export mix to the Eurozone, China, and Japan is…well… more mixed. Services, at around 40%, account for more of our trade to the Eurozone and Japan than in our overall trade mix. In China, however, an above-average 78% of our exports are goods. All else being equal, an unexpected and permanent shift higher in economic growth for trading partners like China, the Eurozone, and Japan should boost our exports to those nations over time and, in turn, our GDP. But it is important to note that outside of recessions, net exports rarely add more than 0.5% to GDP growth. So while we spend a great deal of time discussing the health of the economy in China, the Eurozone, Japan, and emerging markets, the economic prospects of our nearest neighbors (Canada and Mexico) have a bigger influence on our overall exports.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments and exports less imports that occur within a defined territory.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

International investing involves special risks, such as currency fluctuation and political instability, and may not be suitable for all investors.

Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) is an indicator of the economic health of the manufacturing sector. The PMI index is based on five major indicators: new orders, inventory levels, production, supplier deliveries and the employment environment.

Markit is a leading, global financial information services company that provides independent data, valuations and trade processing across all asset classes in order to enhance transparency, reduce risk and improve operational efficiency. The Markit Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMIT) is a composite index based on five of the individual indexes with the following weights: New Orders – 0.3, Output – 0.25, Employment – 0.2, Suppliers’ Delivery Times – 0.15, Stocks of Items Purchased – 0.1, with the Delivery Times Index inverted so that it moves in a comparable direction.

The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) index is based on surveys of more than 300 manufacturing firms by the Institute of Supply Management. The ISM Manufacturing Index monitors employment, production inventories, new orders, and supplier deliveries. A composite diffusion index is created that monitors conditions in national manufacturing based on the data from these surveys.

Challenger, Gray & Christmas is the oldest executive outplacement firm in the United States. The firm conducts regular surveys and issues reports on the state of the economy, employment, job-seeking, layoffs, and executive compensation.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC

Posted in Brazil, China, Durable goods, Emerging Markets, Employment, Europe, Eurozone, Exports, Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), Federal Reserve, GDP - Gross Domestic Product, Goods and Services, India, Institute for Supply Management (ISM), Mexico, Retail Sales, Unemployment, Weekly Economic Commentary | Tagged: Brazil, China, Congress, Durable goods, Emerging markets, employment, Europe, Eurozone, Exports, Fed, federal open market committee, federal reserve, GDP, Goods and Services, India, Institute for Supply Management (ISM), Mexico, Retail Sales, unemployment, Weekly Economic Commentary | Leave a Comment »