The Federal Reserve’s (Fed) policymaking arm, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), announced that it will begin tapering, or scaling back, its bond-buying program known as quantitative easing (QE) at its final meeting of the year last week. The Fed will now purchase $75 billion per month in QE — $10 billion less than the current monthly $85 billion, citing less fiscal drag and the “cumulative progress toward maximum employment and the improvement in the outlook for labor market conditions.”

We believe the Fed made somewhat of a “trade” with the bond market. On one side, the Fed reduced QE by $10 billion per month. Conversely, the Fed delivered a bullish and confident view on the U.S. economy — signaling that it would keep interest rates lower for longer. The stock market was more than willing to forego $10 billion in purchases now (via the taper) in exchange for a bullishly confident Fed that will likely keep rates lower for longer and saw this as a good trade. After all, it is the Fed’s zero interest rate policy, not its soonto- be tapered bond purchases, that has the biggest impact on maintaining lower rates and boosting economic growth.

Fedlines: Ben’s Top 10

Unless the Fed decides to hold a press conference at its next policy meeting in late January 2014, last week’s press conference was outgoing Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s last. During that final press conference, Bernanke was asked about — and weighed in on — several key topics that will likely impact financial markets and the economy throughout 2014. Below, we examine Bernanke’s top 10 answers in his own words at his final press conference as Fed Chairman.

1. Is tapering tightening?

“And so I do want to reiterate that this is not intended to be a tightening.”

2. What advice do you have for Janet Yellen? (If confirmed by the Senate, Yellen will replace Bernanke as Fed Chairman in early 2014.)

“Well, I think the first thing to agree to is that Congress is our boss. The Federal Reserve is a(n) independent agency within the government. It’s important that we maintain our policy independence in order to be able to make decisions without short-term political interference.”

3. At what pace will the Fed taper?

“Sure, on the first issue of 10 billion (dollars), again, we say we are going to take further modest steps subsequently, so that would be the general range.”

4. Would the Fed do more if the economy falters? Would you increase purchases?

“But there are things that we can do. We can strengthen the guidance in various ways. And while the view of the committee was that the best way forward today was in this more qualitative approach, which incorporates elements both of the unemployment threshold and the inflation floor, that further strengthening would be possible and it’s something that is certainly not been ruled out.

And of course, asset purchases are still there to be used. We do have tools to manage a large balance sheet. We’ve made a lot of progress on that. So while — again, while we think that we can provide a high level of accommodation with a somewhat slower place, but still very high pace of asset purchases and our interest rate policy, we do have other things we can do if we need to ramp up again. That being said, we’re hopeful that the economy will continue to make progress and that we’ll begin to see the whites of the eyes of the end of the recovery and the beginning of the more normal period of economic growth.”

“Under some circumstances, yes, … we could stop purchases if the economy disappoints, we could pick them up somewhat if the economy is stronger.”

5. Why Has Recovery Been So Slow?

“It’s — of course that’s something for econometricians and historians to grapple with, but there have been a number of factors which have contributed to slower growth. They include, for example, the observation of financial crises tend to disrupt the economy, may affect innovation, new products, new firms.

We had a big housing bust, and so the construction sector of course has been quite depressed for a while. We’ve had continuing financial disturbances in Europe and elsewhere. We’ve had very tight — on the whole, except for in 2009, we’ve had very tight fiscal policy.

People don’t appreciate how tight fiscal policy has been. At this stage in the last recession, which was a much milder recession, state, local and federal governments had hired 400,000 additional workers from the trough of the — of the recession. At the same point in this recovery, the change in state, local and federal government workers is minus 600,000.

So there’s about a million workers’ difference in how many people are — been employed at all levels of government. So fiscal policy has been tight, contractionary. So there have been a lot of headwinds. All that being said, we have been disappointed in the pace of growth, and we don’t fully understand why. Some of it may just be a slower pace of underlying potential, at least temporarily. Productivity has been disappointing. It may be that there’s been some bad luck, for example, the effects of the European crisis and the like. But compared to other advanced industrial countries, Europe, U.K., Japan — compared to other countries — advanced industrial countries recovering from financial crises, the U.S. recovery has actually been better than most.

It’s not been good. It’s not been satisfactory. Obviously, we still have a labor market where it’s not easy for people to find work. A lot of young people can’t get the experience and entree into the labor market. But I think given all of the things that we’ve faced, it’s perhaps, at least in retrospect, not shocking that the recovery has been somewhat tepid.”

6. What impact has QE had on the economy? Has QE worked?

”Well, it’s very hard to know — in terms of the study it’s very hard to know — it’s an imprecise science to try to measure these effects. You have to obviously ask yourself, you know, what would have happened in the absence of the policy. I think that study — I think it was a very interesting study, but it was on the upper end of the estimates that people have

gotten in a variety of studies looking at the effects of asset purchases.

That being said, I’m pretty comfortable with the idea that this program did, in fact, create jobs. I cited some figures. To repeat one of them, the Blue Chip forecast for unemployment in this current quarter made before we began our program was on the order of 7.8 percent, and that was before the fiscal cliff deal, which even — created even more fiscal head

winds for the economy. And of course, we’re now at 7 percent. I’m not saying that asset purchases made all that difference, but it made some of the difference. And I think it has helped to create jobs.

And you can see how it works. I mean, the asset purchases brought down long-term interest rates, brought down mortgage rates, brought down corporate bond yields, brought down car loan interest rates. And we’ve seen response in those areas as the economy has done better. Moreover, again, this has been done in the face of very tight, unusually tight fiscal policy for a recovery period. So I do think it’s been effective, but the precise size of the impact is something I think that we can very reasonably disagree about and the work will continue on. As I said before, the uncertainty about the impact and the uncertainty about the effects of ending programs and so on is one of the reasons why we have treated

this as a supplementary tool rather than as our primary tool.”

7. Are you concerned about deflation?

“Now, it is true that while we have passed the — or made significant progress on the labor market and growth hurdles, there is still this question about inflation, which is a bit of a concern, more than a bit of concern, as we indicated in our statement. Our outlook is still for inflation to go back to 2 percent. I gave you some reasons why I think that will happen. But we take that very seriously. And if inflation does not show signs of returning to target, we will take appropriate action.”

8. What impact has fiscal policy had on the recovery?

“We’ve had very tight — on the whole, except for in 2009, we’ve had very tight fiscal policy. People don’t appreciate how tight fiscal policy has been. At this stage in the last recession, which was a much milder recession, state, local and federal governments had hired 400,000 additional workers from the trough of the — of the recession. At the same point in this recovery, the change in state, local and federal government workers is minus 600,000. So there’s about a million workers’ difference in how many people are being employed at all levels of government. So fiscal policy has been tight, contractionary.”

9. What is your view on the recent budget deal?

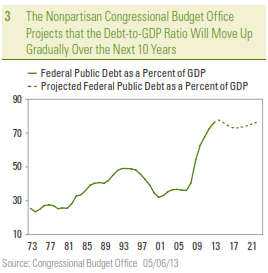

“I will say a couple of things about this deal. One is that, relative to where we were in September and October, it certainly is nice that there has been a bipartisan deal and that it looks like it’s going to pass both houses of Congress. It’s also, at least directionally, what I have recommended in testimony, which is that it eases a bit the fiscal restraint in the next couple

of years, a period where the economy needs help to finish the recovery. And in place of that it achieves savings further out in the — in the 10-year window. So those things are positive things. Of course there’s a lot more work to be done. I have no doubt about that. But it’s certainly a better situation than we had in September and October, or in January during the fiscal cliff, for that matter. And I think it will be good for confidence if fiscal policy and congressional leaders work together to — even if — even if the outcomes are small, as this one was, it’s a good thing that they are working cooperatively and making some progress.

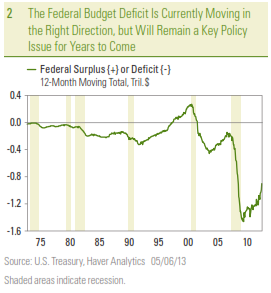

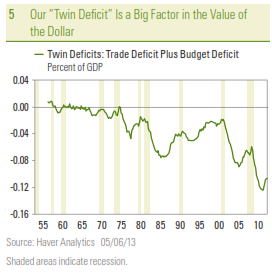

10. Has the large budget deficit weighed on the recovery?

“I mean, investment is driven by sales, by the need for capacity. And, you know, with a slow-growing GDP, slow-growing economy, most firms yet — do not yet feel that much pressure on their capacity to do major new projects. There’s also a variety of uncertainties out there — fiscal, regulatory tax and so on — that no doubt affects some of these calculations…I think there are a lot of factors. Usually you think that the way that a deficit or a long-term debt would affect investment would be through what’s called

crowding out, that it’s raising interest rates. But high interest rates — we may have many problems, but high interest rates is not our problem right now. There’s plenty of — particularly for larger firms, there’s plenty of credit available at low interest rates.”

Fed Watch: Employment Metrics

Outside of “Ben’s Top 10,” we learned that the Fed is indeed watching the employment metrics that we have written about several times this year:

- The quit rate;

- The hiring rate;

- Job openings;

- Wages;

- Long-term unemployment; and

- The participation rate.

Fed Watch: Inflation Factors

On the inflation front, Bernanke opined that some special factors are holding inflation back now and that inflation may pick up in the coming months. He said the FOMC is watching:

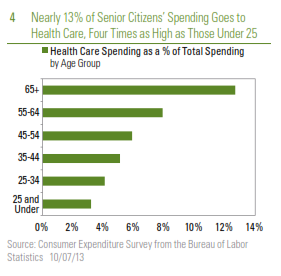

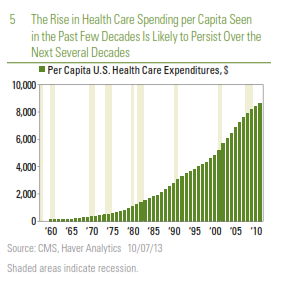

- Health care costs;

- Inflation expectations (as measured by markets and surveys of individuals and professionals);

- Wage inflation;

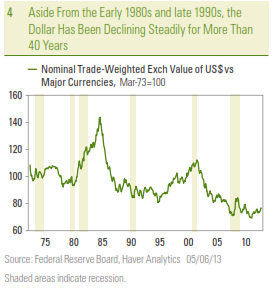

- U.S. and international GDP growth.

The Fed delivered a holiday surprise for the market — a bullish forecast via a signal that it will remain “highly accommodative” with low interest rates for longer . As we have discussed, we view the Fed’s decision as reaffirming our outlook for accelerating economic and profit growth in 2014. We continue to believe 2014 marks a return to a focus on the fundamentals of investing.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

Stock investing involves risk including loss of principal.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is

not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC