Deficit Distraction

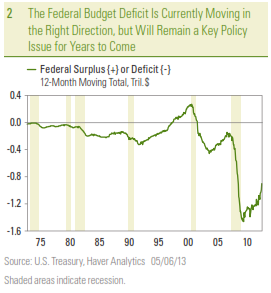

In the 12 months ending July 2013, the federal government spent $3.4 trillion and took in $2.7 trillion in revenues, making the federal deficit (revenues less spending) about $725 billion, the smallest deficit recorded since late 2008. At just 3.5%, the deficit as a percent of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) over the past 12 months was also the smallest since late 2008, and stands in sharp contrast to the 10% deficit-to-GDP ratio posted in fiscal year (FY) 2009 ending September 2009 [Figure 1].

The story is much the same fiscal year to date in FY 2013, which ends on September 30, 2013. In the first 10 months of FY 2013, the budget deficit was $607 billion, or roughly 3.6% of GDP. Outlays have totaled $2.9 trillion and revenues have totaled $2.3 trillion. The first 10 months of FY 2013 saw the smallest deficit and deficit to GDP of any comparable period back to the first 10 months of FY 2008. An improved economy, a stronger labor market, spending cuts from sequestration, and recent changes to tax rates account for most of the improvement, although a few “one-time items” have also played a role. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which produces an excellent update on the progress of the federal budget every month called “Monthly Budget Review” (see http://www.cbo.gov), continues to project that the budget deficit in FY 2013 will total $642 billion, or around 4.0% of GDP.

What’s Driving the Improvement in the Deficit?

Fiscal year to date in 2013, federal revenues are up 14%, while spending is down nearly 4%. Combined individual income tax receipts — which account for around 85% of federal revenues — are up 15% in the first 10 months of FY 2013 versus the same period in FY 2012. Personal income taxes account for roughly 50% of Federal revenues while taxes withheld for Social Security and Medicare account for 35% of federal revenues. A better labor market (2.3 million net new jobs were created over the past 12 months) and rising wages (wage and salary income, as measured by the monthly report on personal income and spending, is up 4% year over year), account for some of the gain. The fiscal cliff — the expiration of the Social Security payroll tax cut in January 2013 and the increase in tax rates for incomes above certain thresholds — have also boosted revenues. The rising equity market has also accounted for some of the gain in individual tax revenues: equity markets hit new all-time highs in the first half of 2013 and investors may set aside tax payments after exercising stock options or selling stocks. Corporate profits are at record levels, and corporate tax receipts are up 17% in the first 10 months of FY 2013 versus the similar period in FY 2012. Corporate tax receipts account for 10 – 15% of federal tax revenues [Figure 2].

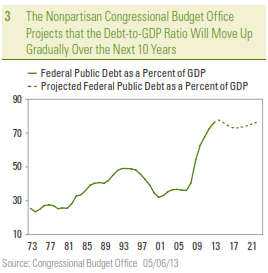

At $2.9 trillion, federal budget outlays in the first 10 months of FY 2013 were $90 billion (or 4%) lower than in the same period in 2012. Not surprisingly, given the solid performance of the labor market noted above, federal spending on unemployment benefits was down a whopping 24% in the first 10 months of FY 2013, while defense spending (impacted in part by the sequester) fell 7%. Federal spending activities outside of defense and entitlement programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid fell 3% in the first 10 months of FY 2013 versus the first 10 months of FY 2012, but that figure is skewed lower by payments received by the federal government from the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and big payments from the large, quasi-government mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac that were at the center of the financial crisis. Despite the distortions, the sequester is having a modest impact in controlling non-defense discretionary spending. Interest payments on the public debt totaled $216 billion in the first 10 months of FY 2013, down 2% from the $222 billion in the similar period of FY 2012 [Figure 3].

Warning Signs

Some warning signs exist in the otherwise positive budget picture thus far in FY 2013 however, and if these warning signs continue to be ignored by policymakers, the near-term improvement in the budget picture is not likely to last. FY 2013 to date, federal spending on mandatory programs (payments set by formula written into the law) like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid is running above the pace of nominal GDP growth. Federal spending on Social Security benefits is up 5.4%, nearly twice the rate of nominal GDP growth over the past year (2.9%). Similarly, spending on Medicare is up 3.0% in the first 10 months of FY 2013, while Medicaid spending is up 5.7%, also about twice the rate of nominal GDP growth. The non-partisan CBO expects the improvement in the federal budget deficit to continue over the rest of this fiscal year, and for the next several fiscal years as well, through FY 2015. By then, the CBO expects the deficit as a percent of GDP to fall to 2.0%, the smallest since the 1.2% deficitto- GDP-ratio recorded in FY 2007, the last fiscal year prior to the Great Recession. From a 2.0% deficit-to-GDP ratio in FY 2015, the CBO projects that under current law, the deficit will increase to 3.2% in FY 2020 and to 3.5% by FY 2023, the last year the CBO makes a projection.

Most of the deficit deterioration in the latter half of this decade and the first half of the next occurs as a result of deterioration in the structural deficit, i.e., spending on mandatory programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid far outstripping the pace of GDP growth, mainly due to an aging population. The CBO projects that tax receipts targeted for use by those programs will only grow at the same pace as the overall economy over the next 10 years or so. Thus, the risk is that Congress and the general public will be distracted by the rapidly improving near-term budget outlook, and will not address the longer-term structural budget problem quickly enough to head off a worsening, long-term budget deficit.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investment(s) may be appropriate for you, consult your financial advisor prior to investing. All performance reference is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested into directly.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the monetary value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, though GDP is usually calculated on an annual basis. It includes all of private and public consumption, government outlays, investments and exports less imports that occur within a defined territory.

The economic forecasts set forth in the presentation may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful.

International investing involves special risks, such as currency fluctuation and political instability, and may not be suitable for all investors.

Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) is an indicator of the economic health of the manufacturing sector. The PMI index is based on five major indicators: new orders, inventory levels, production, supplier deliveries and the employment environment.

Markit is a leading, global financial information services company that provides independent data, valuations and trade processing across all asset classes in order to enhance transparency, reduce risk and improve operational efficiency. The Markit Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMIT) is a composite index based on five of the individual indexes with the following weights: New Orders – 0.3, Output – 0.25, Employment – 0.2, Suppliers’ Delivery Times – 0.15, Stocks of Items Purchased – 0.1, with the Delivery Times Index inverted so that it moves in a comparable direction.

The S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index measures the change in value of the U.S. residential housing market. The S&P/Chase-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index tracks the growth in value of real estate by following the purchase price and resale value of homes that have undergone a minimum of two arm’s-length transactions. The index is named for its creators, Karl Chase and Robert Shiller.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial.

To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor, please note that LPL Financial is not an affiliate of and makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not FDIC/NCUA Insured | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | May Lose Value | Not Guaranteed by any Government Agency | Not a Bank/Credit Union Deposit

Member FINRA/SIPC